Maino De Maineri - Physician to The Bruce

On the pages of the Edinburgh University press we found an interesting link to Robert the Bruce's Italian physician, Maino De MainieriThis abstract was given and we will link the access to the full article below. Unfortunately the full article is not freely available:

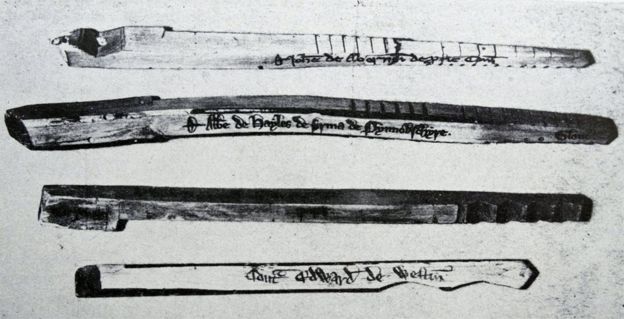

This article pieces together evidence from fourteenth-century Scottish royal records to identify one of the physicians to King Robert I as the Milanese Maino de Maineri (ca 1295–1368), regent master of the University of Paris and later court physician and astrologer to the Visconti rulers of Milan. The implications for the history of medicine in medieval Scotland are significant, suggesting that, at least at court level, Scots demanded and could afford and attract a high quality of medical treatment. Also emphasised are the strong links that existed between Scotland, Ireland and continental Europe, through the travels of physicians and the transmission of medical literature. Three fifteenth-century manuscripts of one of Maino's works are used as an example of just this type of transmission. The article urges a reevaluation of medical culture in medieval Scotland.

Maino De Maineri - Der Leibarzt von Robert the Bruce

Auf den Seiten der Edinburgh University Presse fanden wir eine interessante Artikel über zu Robert the Bruces italienischem Arzt Maino De MainieriDiese Zusammenfassung ist aktuell frei erhältlich und wir werden den Zugang zum vollständigen Artikel unten verlinken. Leider ist der ganze Artikel nicht frei verfügbar:

Dieser Artikel vereint Hinweise aus den schottischen königlichen Schriften des vierzehnten Jahrhunderts, um einen der Ärzte am Hof von König Robert I. den Mailänder Maino de Maineri (ca. 1295-1368), Regentenmeister der Universität Paris und später Hofarzt und Astrologe des Visconti-Herrscher von Mailand. Die Implikationen für die Geschichte der Medizin im mittelalterlichen Schottland sind bedeutsam, was darauf hindeutet, dass zumindest auf dem Adelsniveau, Schotten sich die höchste Qualität der medizinischen Behandlung leisten konnten. Ebenfalls hervorgehoben sind die starken Verbindungen zwischen Schottland, Irland und Kontinentaleuropa, durch die Reisen von Ärzten und die Übertragung von medizinischer Literatur. Drei Manuskripte des fünfzehnten Jahrhunderts eines der Werke von Maino werden als Beispiel für diese Art von Übertragung verwendet. Der Artikel drängt auf eine Neubewertung der medizinischen Kultur im mittelalterlichen Schottland.

Links:

The main article / der ursprüngliche Artikel

Wikipedia Maino de Maineri